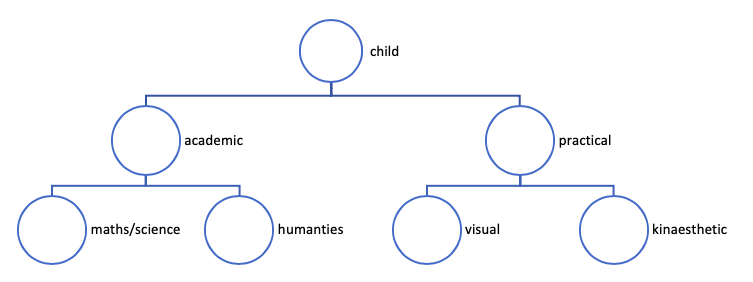

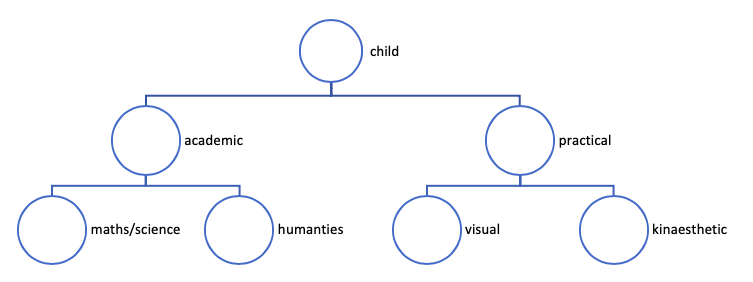

I have often feared that school teaches students that they are not good at things; that school acts as a filter rather than a capacity builder. Even as school has become much more inclusive, providing a range of pathways and inviting universal senior secondary completion, there are a lot of types or categories of students that can emerge from education, and not all of them are valued equally. For example, students can be divided by school into the practical and the academic; the kinaesthetic, the visual and the auditory; maths students and not maths students, humanities or not humanities students. I fear that some students go to school and learn that they are not good at learning – what sort of an education is that? Are our systems and practices building the capacity of students or providing some kind of dichotomous key that asks a range of questions that students pass or fail to determine which category they fall into. If so, these tests are just inventions sorting students by some arbitrarily chosen criteria – like achieving 50% of the marks on a test.

Schooling unfortunately, can become a game of fitting square pegs to round holes.

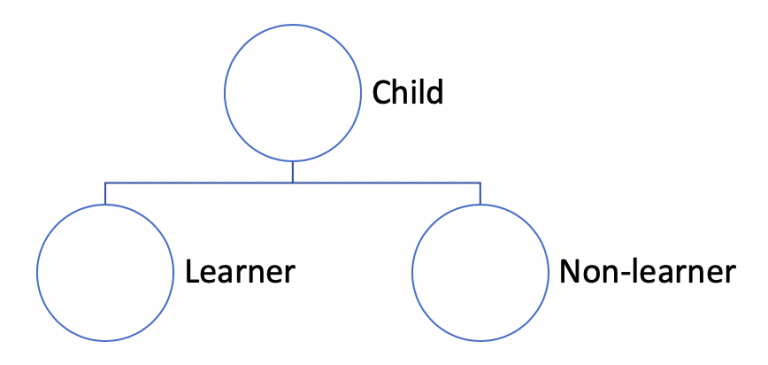

Schools must not be places where students are sorted into learners and non-learners.

It is interesting to me that in our system, students who learn that they are not good at something do less of it. If in their years of junior and middle schooling they do not perform well, for whatever reason, on tests of mathematics, or science, or art, or whatever, they learn less or perhaps none of that subject in senior secondary, instead they focus on areas that they did well at or that are seen to be easier for students who have not performed well. There are lots of good reasons for this, but it does distinguish senior secondary school from the more general notion of school as a place where young people go to learn the foundational knowledge for participating in society. Remarks like “what do they teach students in school these days” can only be a criticism of primary and middle schooling, where most students are expected to learn the same things.

When aspects of senior secondary education move down to younger years of schooling with early access to senior secondary subjects and extensive elective programs, the understanding of the purpose of school is challenged further. As students can choose to learn, or be chosen to learn, knowledge that they are interested in or they are perceived to be more capable of learning, they are not only categorised but shaped to fit categories. That could be seen to be a problem when we realise that the categories available are different in each school because the opportunities and subjects available are different.

The prime focus of schools, teachers and education systems, in my view, needs to be on learning rather than categorising. Failure should be a challenge, an opportunity to learn more, not to be selected into a category or to learn that they cannot learn. Success should be an invitation to look for greater challenge. School should not be about sorting into predefined (but arbitrarily defined) categories but about person making. Every person is unique and we do not know what they will be or what they can be. School is not like any other industry because the products are all unique and cannot be planned in advance. Attempts to predefine the products of schooling, what a student will be able to know and do, puts constraints on the learning and disastrously makes some students nonlearners

I have enjoyed reading an interview of Ivor Goodson by Ragna Adlandsvik. It includes this exchange where they are comparing education to art:

- …”RAGNA: And all kinds of art are dialogic in a way. Art invites us to answer. It doesn’t have the whole truth. Art asks questions and is waiting for an answer.

- IVOR: I think you are mentioning two of the criteria of good education. One is: it invites us, namely, it is inclusive, not exclusive. But the other side of it is that knowledge and education should be tentative, because to be inclusive, you have to be tentative. If you already have the answer, as a pedagogue, or teacher, or writer, if you have the final solution, that is exclusive. Then you are the exclusive expert. I would want to be the inclusive, slightly tentative pedagogue. Tentativeness is the way I see knowledge. Knowledge is conditional, contextual. It works differently for you, as it does for me, in different situations. So it is a negotiated product, a tentative product, it is a very fragile, but loving product. It is not a scientific box. It is something that moves around, it is tentative, it is engaged, but in a fragile way, but can move mountains if it is engaged. And that is how I see knowledge: inclusive and tentative, not exclusive and final.

- RAGNA: And that is a place where art and education meet. They ask questions, but they don’t have the answer; that is for the other to find out.

- IVOR: Always for the other to find out. Everybody has a different kind of answer. If you could find the right question, you are more than halfway done. The answer is something that is negotiated. In the end the learner has to find… That is always difficult to understand, because it sounds like an educational license, which means that the learner always knows best. I am not saying that at all. And I am saying that there is a massive role of the pedagogue to influence, to question and to set up of the process. But at the end of the day, it is always a personal thing; it is a personal decision whether you learn or not. You have the final arbitration of whether you choose to engage to learn, or you choose to switch off. And I am saying that exclusive, final products, sort of lecturing, more than anything, switches off the learner. So if teachers think they have the absolute complete final answer, there is no grade to switch off. And there is no grade to switch off in the conversation between you and I, for me to sit here and tell you all the answers, and you to listen. You would be out of the room in no time. But if we have a conversation, and an equal one, and if it is dialogic, then we are both engaged, we are both contributive… (Goodson, 2011)

Let’s invite students to learn, whatever their starting point and rates of learning. Let’s also allow room for surprises, new knowledge and perspectives, and celebrate them rather than centring school about judging the success we have of squeezing emerging persons into holes that we have prepared for them in advance.

Goodson, I. (2011). Life politics. [electronic resource] : conversations about culture and education: Rotterdam ; Boston : Sense, c2011.

Ross Phillips

Senior Dean of Learning, Research and Innovation