Grappling with this notion of the self, both ‘Daddy’ and ‘Mirror’ speak to Plath’s own experiences as the victim of a patriarchal society, “stuck in a barb[ed] wire snare” desperately “searching [her] reaches for [who] she really is.” Confronted by those expectations imposed upon the poet across all facets of her life, as a daughter, mother and a young woman, Plath’s visceral tone condemns a society that aspires to threaten a woman’s identity wherever possible. Consumed by this pressure, the poet’s scathing critique is ultimately reflected within her own identity, fulfilling a self-perpetuating cycle of deprecation.

Commenting on those external threats that come to define one’s own reflection, Plath’s exploration of her personal relationships tell the story of a woman whose identity is defined by those to whom she is related. The poet’s fraught and complex relationship with her father, examined through the poem ‘Daddy’, presents a cynical understanding that in order to simply survive as a young woman within an oppressive society, she is forced to negate her own identity. At the core of Plath’s grief is an irrational belief that in asserting her poetic voice where it once couldn’t “worm through”, she has “killed one man” if not two. Aware of her personal affliction, Plath appears deeply critical of a society that allows women to feel this sense of guilt in simply existing. Carrying this sense of grief across her poetry, Plath’s innate desire to “get back, back, back to” her father highlights the grasp that these relationships hold over her identity. Drawing a comparison between distinct memories of her father and those narrative figures central to one’s childhood, Plath likens her father to two key mystical creatures; the devil with a “cleft in [his] chin” and a vampire drinking her blood, biting her “pretty red heart in two.” Employing this childlike description, rendering her father as the villainous figure of the poet’s life, Plath seeks to highlight the emotional significance of his death as an experience that she could never escape and perhaps one that comes to define the rest of her life. Extending this idea of oppression through identity, Plath maintains a deep criticism of societal beauty standards that “reward [the poet] with tears”, struggling to identify the reflection she is met with, staring blankly “day after day”. The poet’s own fears of ageing are central to her work in ‘Mirror’ and are reflected through the use of enjambed phrases, highlighting the inevitable progression of time and the looming threat that the course of life poses for a young woman. This imminent fear of youth receding is indicative of the influence these standards hold and their ability to dictate a woman’s value. The “four-cornered” view of the mirror presents the boundaries to which Plath’s reflection is restricted and is now herself, unable to see beyond. This societal inability to extend our understanding beyond the façade of appearance is something Plath calls into question, highlighting the fragile nature of identity when built upon societal conventions.

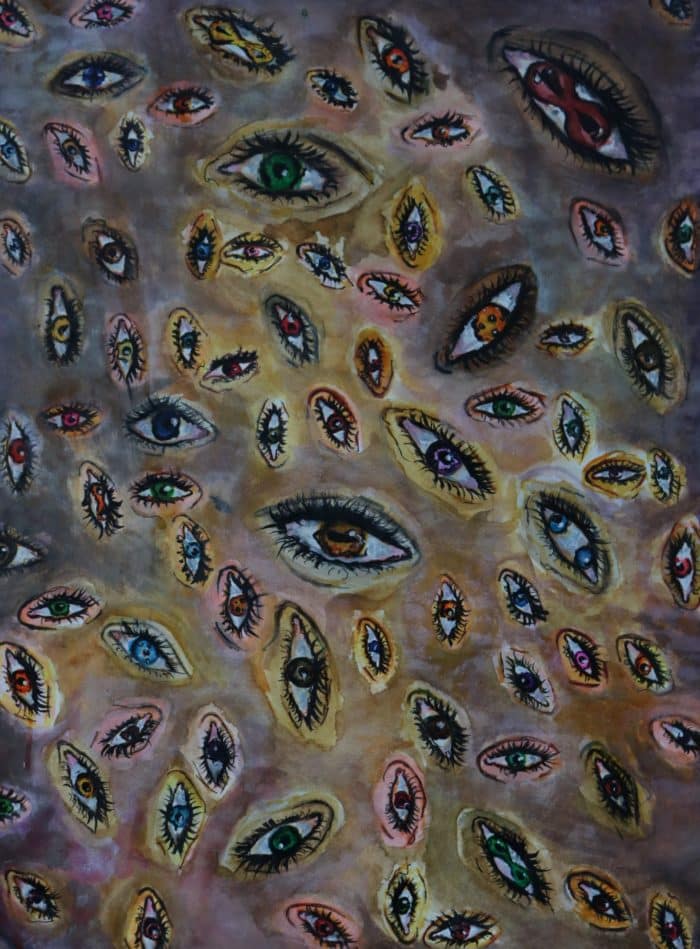

As a prominent aspect of Plath’s poetry, her idealised view of the world, recognising the “eye[s] of [those] god [like]” figures as omnipresent features of her life, the poet’s acquiescent nature perhaps poses the greatest threat to her identity. The power afforded to her father in death casts a dark shadow over Plath’s life “for thirty years”. Suffocated and oppressed, the poet likens her father’s “marble-heavy” and lifeless influence to the authority of a higher order. This idea reverberates across her poetry, and Plath’s personification of the mirror, “silver and exact”, with an “eye of a little god” illustrates her own ability to attribute significance and meaning to an inanimate object. This anthropomorphic metaphor seeks to focus in on the power offered to these trivial objects and criticise our willingness to let them determine our identity. Highlighting a belief that “in [her] has drowned a young girl, [where] an old / woman” now rises, Plath engages an understanding of Greek mythology. This fabled allusion to the story of Narcissus in which a young man falls in love with his own image, reflected in a pool of water, criticises the poet’s own vain and narcissistic proclivities. Mirroring this idea of replication, is Plath’s own desire to “make a model” of her father, “a man in black with a Meinkampf look” with a “love of the rack and the screw”. Identifying these similarities between her father and husband, Plath illustrates the nature in which she has become victim to the violence and sexual desires of the men in her life. Plath’s use of this double entendre conveys an understanding that this fine line between violence and passion has not only come to define the poet’s own identity, but also her relationship with another. The use of a caesura with a forceful break in the metrical foot of Plath’s writing reflects the gap in her own heart. Supporting this idea that the mirror has now become “part of [her identity]”, Plath criticises an emotional void that is filled with her own obsession. Allowing her youth to pass her by, Plath’s “flicker[ing]” sense of self has transcended beyond reality. The use of this onomatopoeic phrase mimics the sound of the word itself, dragging attention towards the fragility of the poet’s identity. Trapped within her own desires for a youthful appearance, Plath’s readiness to “turn to those liars” presents an introspective criticism for the deception that subtle light affords an ageing woman. Those dualities referenced across Plath’s body of work highlight the conflicting identity of a woman standing at the crossroads between “love and dislike”. Maintaining this sense of polarity across both poems, Plath establishes the imminent conflict of personally identifying as the “young girl” she yearns to be, or the “old woman” she sees within her own reflection.

Presenting her flickering identity at the centre of her work, Plath extends criticism towards those external threats, “drowning” a woman’s perception of herself. The poet’s exploration of the idea of the self ultimately shifts towards a brooding consideration of a willingness to allow societal expectations to dictate her identity, standards which she is neither unable to meet, nor defy.

Written by Elizabeth O’Sullivan, Year 11.