There has been much said about the skills needed to thrive in the workplace that the students of today will enter. One thing that seems almost certain is that it will not be enough to learn some skills at school then apply them throughout a working life.

As a result, transferable skills such as creativity, collaboration, critical thinking and communication (the four C’s) are highly regarded. There is little doubt that these are skills that our students will need in their careers, however, there is a lack of evidence that they are transferable. The ability to think critically in an area requires a lot of expertise in that area, as does communication. Collaboration can look quite different in different fields and does the creative genius that is so expressive in a great work of Art assist the same person to have creative insights in Science? Not typically. As our roles change through our careers as the result of technological and social changes we do need to adjust. Dr Jared Cooney Horvath, Harvard trained Educational Neuroscientist at the University of Melbourne describes the ability to learn as the only known truly transferable skill. As our jobs change, we cannot just seamlessly apply our existing skills of critical thinking and communication in the new context, we need to learn.

Dr Horvath led our current Year 9 students last year in an extended program called Cognizance, helping the students understand how their brains work and how they can use them effectively to learn. His teaching fits nicely with the growth mindset thinking that we often refer to at Strathcona. It also fits with what I recently addressed with Year 10, 11 and 12 parents at the recent Parent Information Night.

The points I made at the evening are I believe important for all age groups. Firstly, given that learning is our focus, feedback is incredibly important. Often grades can overshadow feedback. The focus can sway to how good the student is when I would argue it should be focussed on what the student can learn from the situation. That thinking has important implications for how students respond to marks. If a student is regularly achieving 100%, I believe that the student is not receiving an important part of feedback – what to work on to improve. Both Dr Horvath and Professor Carol Dweck, the author of Growth Mindset say that all students are able to learn. If the result of a test or assignment mark is that the students feel they are not good learners, the test has been destructive. There are other interpretations of a mark that is perhaps not as high as the student would like. These include that the student was not well prepared, did not address the criteria, was not ready to achieve at a high standard for whatever reason. It is quite unreasonable to think that every student will be able to perform at the same level on the same day. For some, that level might not be attainable for years but most of the material assessed at school will be attainable eventually for most who persist.

I made further points about learning:

Consistency – learning is more effective when application is consistent over a period of time. An example of this is storing facts in memory. Most people do not just read their times tables once and have them committed to memory. They need to review them again and again until they are an automatic part of their thinking. Those who do not put in this effort will find Mathematics to be harder because of the extra processing they need to do with every problem. To commit facts to memory is most effective when students are required to recall them. It is much better to try to recall facts after reading them, than to simply keep reading over the notes. Again, this should be spaced over a period of time, the day it is learnt, the next day, the next week, for example. Recalling the facts helps commit them to memory and also allows the student to focus more attention on those areas she cannot recall, which leads to the next point.

Prioritising – there is never enough time to do all the things we feel we need to do. With limited time to study, students need to spend that time doing things that give them the most learning gains. Using effective memorisation techniques is one point, but there are many others. How much time is spent on activities that appear to be schoolwork, or homework, but achieve no or little learning? Some students spend a lot of time just preparing to work, others are always ready and get straight to it. Some spend a lot of time writing or decorating or rewriting when that is not required. Students should start by being clear about what they are meant to be learning and work hard to stay focused on the criteria.

Intensity – a key difference between students is the intensity they work at. I would argue that it is better to work in 20 or 30 minute chunks of focused, undistracted time than hours of half pace in front of the television. Which leads to the

next point.

Removing distractions – Those intense chunks of time have total absence of phones, messages, emails, music, television, conversation, toilet or food breaks. The time is for work and the necessary breaks for the other things are no more than half an hour away. Neuroscience has exposed the myth of multitasking. If we try to do more than one thing at a time we really switch between the two tasks rapidly. However, in switching, time is lost and it takes much longer to achieve the same result as it would if attending to both tasks properly. Learning is difficult and requires full attention.

Sleep – The Dux of the School 2018, Olivia Muirhead told the students at the Scholars Assembly a few weeks ago, how, throughout Year 12 she went to bed at 9pm each night and rose at 6am for a quick jog before going to school. This was a diligence that few students that age can match, but the science tells us again and again of the importance of that amount of sleep each night to help manage stress and to help lay down memories and learning from the day.

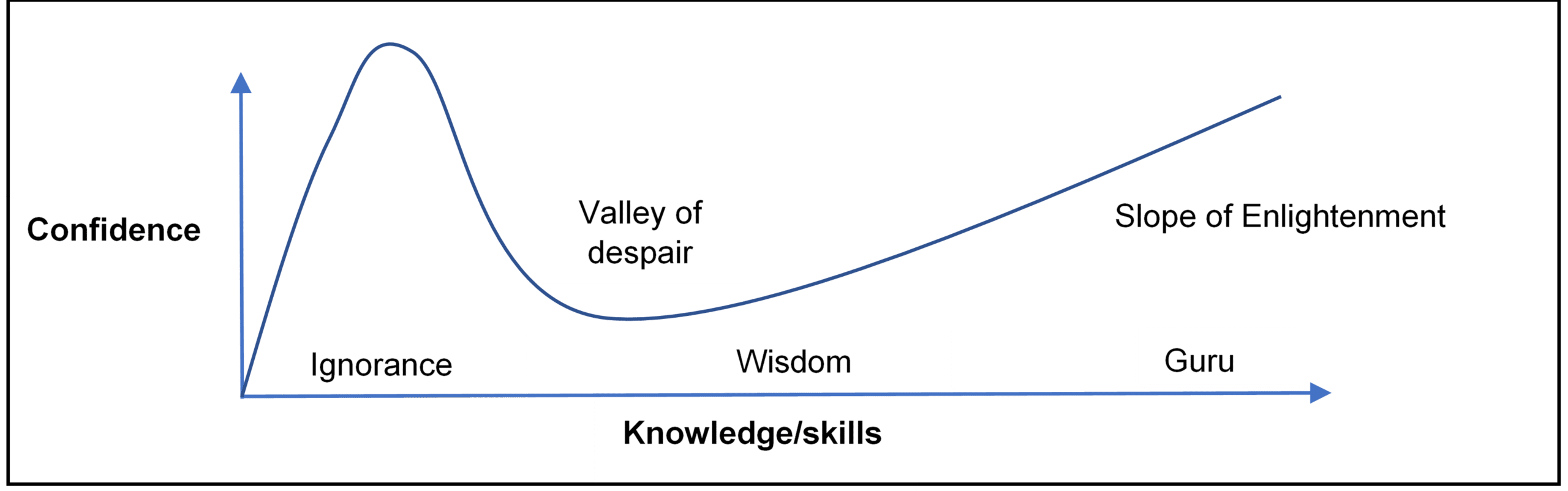

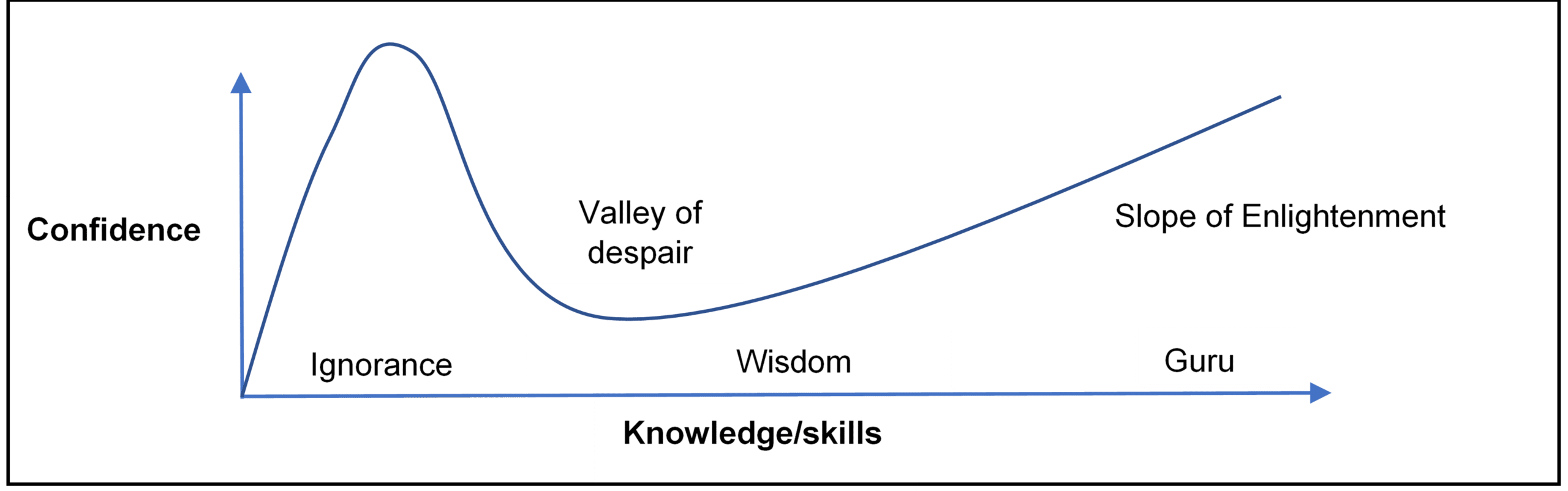

I finished my presentation with a finding that I enjoy sharing with students. The Dunning-Kruger effect is the finding of studies into people’s perception of their capabilities. In short, those with little knowledge have confidence in their understanding way out of proportion to their capability. As they gain in knowledge, their confidence does not keep pace as they learn more about the complexities of the situation.

This graph is a popular way of describing the Dunning-Kruger Effect. Essentially it says that those who know little or are incompetent, believe that they know much more and are much better at what they are doing than they are. This can be understood by realising that at this stage you do not know enough to know what you do not know.

We might be reminded of Alexander Pope, who wrote in 1711:

A little knowledge is a dangerous thing

Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring

There shallow drafts intoxicate the brain,

And drinking largely sobers us again.

Sobers us indeed for that naïve confidence that is replaced as we gain more knowledge. We see that there is a lot we don’t know and we start to realise that we don’t know what we don’t know. We have transitioned from ignorance to wisdom and the cost is that our confidence plummets. As we persist with resilience, we move on from the valley of despair to climb the slope of enlightenment.

This path is one that the students will take many times as they move through school. The crisis in confidence that comes from knowing that there is a lot they don’t know is essential and normal. It does not mean that they are incapable or that something has gone wrong. It is part of the learning journey. Ignorance is bliss, according to another 18th century poet, Thomas Gray. We need our students to have the faith in themselves, their teachers and their school, the courage to face the challenges and the optimism to know the rewards of pushing on.

Part of the trick is to think of the world in terms of probabilities rather than certainties. Those who think in terms of certainties may panic the thinking that because they know that there are things that they do not know, the exam will be full of them. By contrast, those who think in terms of probabilities understand that there are always things that they don’t know but if they study the course and past exams or tests, the chances of being confronted with questions that they are not going to be able to answer becomes smaller.

I encourage all students to remember that their job at School is to learn, not to get a grade. As long as they are continuing to learn, and to become life-long learners, they will be developing the capacity to succeed at school and beyond.